|

|

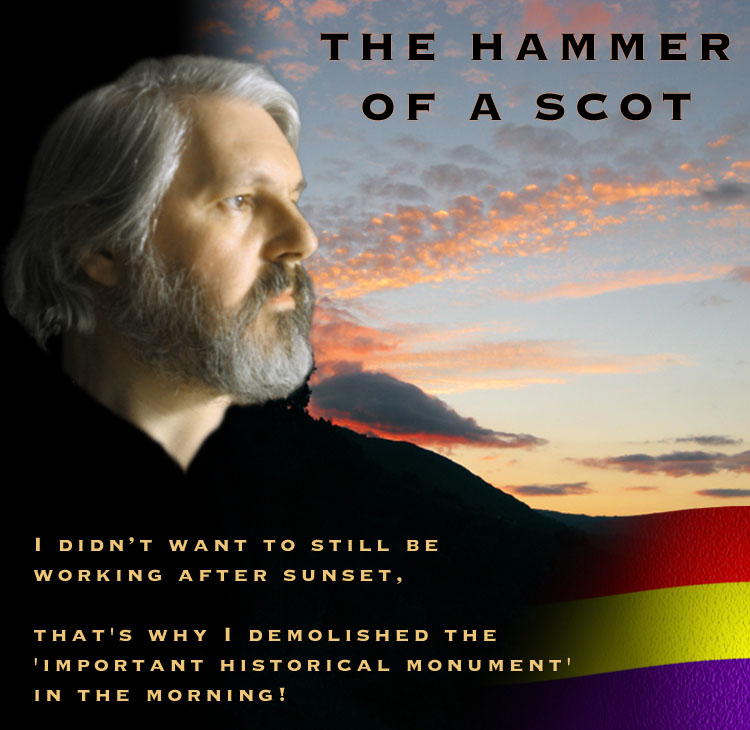

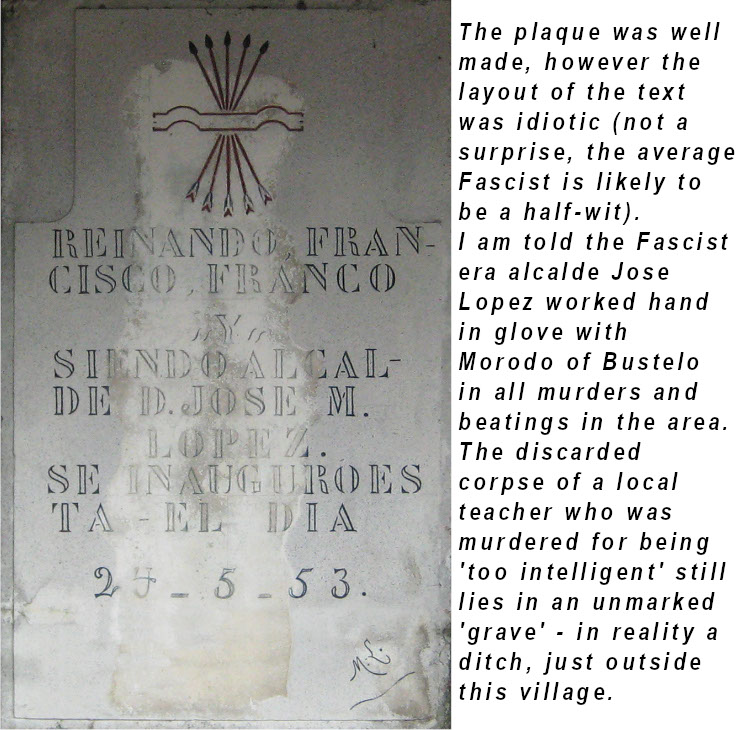

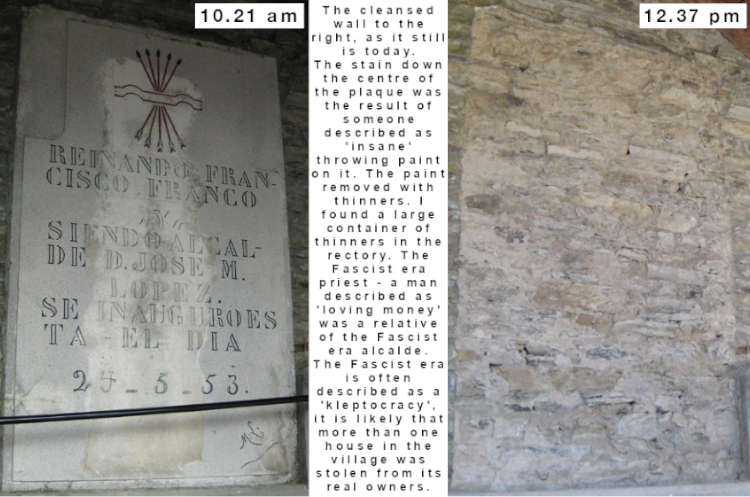

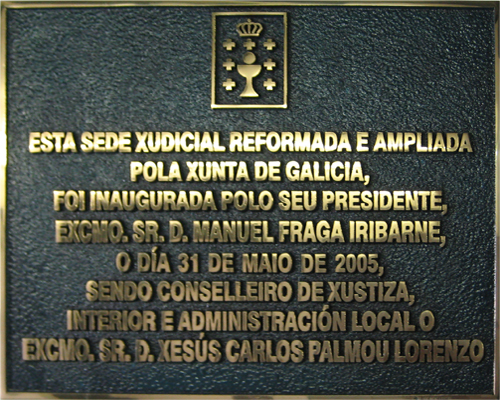

I was looking for peace and quite. On that sunny day in May of 2009 the only sound was the suppressed 'shhh' of insects - a sound which like that of the sea on a beach becomes effectively inaudible within moments. There is a great view; not drop-dead-gorgeous but attractive and varied. The house is surrounded by hills. With the exception of the hill behind the house all are far enough away that the horizon is not much above eye-level, consequently there is a great expanse of sky. There is also a lake below. Had it been a rainy day I would have spent more time looking at the house, and perhaps have understood the scale of work needed to make it fully habitable. Five years on I am inclined to consider renaming it Colman's Folly. There is a saying 'Be careful what you wish for, you might get it!', and I recall once sleeping on a park bench in Buxton, and, looking up at a real folly on a near hilltop, thinking "I wouldn't mind having a folly - it would be interesting". The negotiation over price with the two agents was brief, and having agreed it I held my hand out to the Spanish agent to seal the agreement. The English agent cautioned me against shaking hands "In this part of the world a handshake is regarded as binding." I said that was fine by me, I had assumed it was binding. Remember that statement; "In this part of the world a handshake is regarded as binding." - we'll be coming back to it later. Five minutes after the handshake I regretted making it. We had entered the village from the western end, as we left from the eastern I was appalled to see a large Fascist plaque above the fountain. An equivalent would be to see a Nazi plaque in a German village. The Fascist military rebellion in Spain overthrew the elected civilian government with the aid of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, and the active co-operation of the Catholic Church. The Fascists used murder, rape and torture to terrorise the civilian population. Indeed, they boasted of their near medieval barbarity. There are believed to be well over 100,000 murder victims of the Fascists still lying in unmarked mass graves all across the country. Had I seen the plaque I would not have agreed to buy the house. Under no circumstances would I move to a village with such a sickeningly offensive artefact on display. Having given my word with a handshake to buy the house, I considered the option of paying the non-returnable deposit and then forfeiting it - something which I could not afford to do. While pondering this option I discovered a law had been passed in 2007 rendering these artefacts illegal and requiring their removal. Confident that the plaque would be gone by the time I moved in I completed the purchase. In December 2009 I moved in. I was perplexed to find the Fascist plaque still in place, and promptly visited José Manuel Braña Pereda, the alcalde (mayor), to find when it was to be removed. He told me that the wording of the plaque was ironic and therefore the plaque was not illegal and would not be removed. My view of the wording was that it was offensive, sycophantic, and had been written by an idiot. However accepting that there could be some subtle idiomatic construction in the wording that was beyond my understanding of the language, I gave him the benefit of the doubt at that time.  Shortly thereafter I was able to get a bilingual resident of a nearby town to look at the plaque. His view of the plaque echoed mine; the wording was sycophantic and written by someone not very bright. The 'ironic' ploy, he said, was used as a means of avoiding their legal obligations by councils who did not want to pay the cost of having the illegal objects removed. I suggested that there might be some particularly local aspect to the 'irony' which was escaping both of us. He was quite certain there was not. Over the next 15 months I raised the issue of the plaque with dozens of people in the municipality and the two nearest towns. With the exception of three or four who made no comment, all the others made the same points; the wording was not and never had been 'ironic', but was offensive, and that the plaque was illegal and should be removed. One of those who did not comment I now know to be the wife of a Fascist - presumably not happy that that which they took pride in was being explained away as a joke. During the conversation her elderly husband was staring off into space; I don't know whether he was not commenting, or simply not listening. The other 'no comment's followed this form: Me - "The alcalde says the wording on the plaque is ironic." Respondent - "Yes, the alcalde says the wording on the plaque is ironic." The fifteen months of information gathering came to an end when the alcalde rang my doorbell and asked me to vote for him. I raised the issue of the illegal plaque; I pointed out that none of the many people I had spoken with had agreed with his 'irony' claim, and that with the exception of three or four who made no comment all had stated the plaque was illegal, offensive and should be gone. He did not dispute this, but asked what I wanted to be done. [At this point it is worth noting that subsequently he claimed not to have understood what I was saying, claimed never to have acknowledged the illegality of the plaque, claimed never to have agreed to make changes to the plaque, claimed the plaque was not illegal, acknowledged the plaque was illegal, acknowledged (in court after much diversionary waffle) that he had agreed to make changes to the plaque 'to bring it into line with the law' thereby acknowledging its illegality. In my opinion he is capable of contradicting himself within a single sentence. I was asked whether I thought the alcalde was a Fascist. I said I thought he had no politics, but was just stupid. A man who heard my comment tapped me on the shoulder and said "You won't know this, but I was at school with your alcalde and you're quite right, he is very stupid."] In response to the alcalde's question I said the Fascist symbol had to be removed, so too the text relating to the Fascist era alcalde. This would leave the name of the murderous Fascist dictator, the supposed joke 'REINANDO', and the date of inauguration. Next to it was to be erected another large plaque explaining the 'irony' - this to be written in Gallego. The purpose of this second plaque being to allow the alcalde to save face over his 'irony' ploy. There was also to be a smaller plaque with translations of the Gallego text in Castilliano, English, French and German. For someone who did not understand what I was saying he found no difficulty in plucking understanding from the ether, and asked me why the choice of Gallego. In respect to local people, and, pointedly, because the Fascists banned its use, I explained. In another supernatural act he again plucked meaning from the ether and asked why the sequence of other languages. Because, I explained, Castilliano (ie Spanish) is the national language, English is the most widely spoken language on the planet, and with French and German most Europeans would be able to understand the wording. I carefully reiterated all the terms; removal of Fascist symbol, removal of the name of Fascist era alcalde, two new plaques as described. He agreed to all of this and we shook hands on it. Remember that statement from earlier? "In this part of the world a handshake is regarded as binding." - keep remembering it, we're not finished with it just yet. Between then and the elections I had a chance to tell several people of this agreement. The general feeling was 'good progress, but a new plaque explaining a non-existent joke would be a waste of money'. On election day the alcalde looked shifty. I hope he's not thinking of going back on the agreement, after all "In this part of the world a handshake is regarded as binding." I thought to myself.  Of course you will already have deduced he did indeed renege after the elections. On the Wednesday preceding the 75th anniversary of the start of the Civil War I went to find out if the work could be done before the anniversary. The alcalde had gone home for the day, but I met one of the other three members of the Council, José Antonio Fernández Cancio, who was responsible for public works. He told me the council could not afford to do the promised work. I asked if the only problem with doing the work was the cost, and he said yes it was only a question of money. This tallied with the comments I had heard many times before. I had an intelligent, imaginative solution to this impasse: if it was only a question of money I'd be very happy to do the job of removing the entire plaque (as the law requires) free of charge. Envisioning that the job of removing the plaque would take many hours with a cold chisel, and that a power hammer would speed up the work, I made my offer. "José, if its only a problem of money, tomorrow with a council hammer I will remove the whole plaque. Not for money, just for the pleasure of doing it. In just one day with a council hammer the plaque will be gone, totally. Yes or no, not for money, just for the pleasure of doing it?" He responded with a gesture which seemed to signify neither 'yes' nor 'no', but rather 'possibly'. Two other people were present, and they immediately launched in "José, José this is a good idea..." the conversation between the three was too rapid and beyond my vocabulary for me to follow in detail, but it was very clearly going in my direction. As it was dithering down I repeated my offer, and this time the response from the councillor was "Si" - and we shook hands on it! You do remember that statement from earlier don't you? "In this part of the world a handshake is regarded as binding." - keep remembering it, we're still not finished with it yet. It was then agreed that he would bring a power hammer to my house the next day. Preferring to get as much of the work done early in the day as possible, before the full July heat arrived, I spoke to him again later and he agreed to bring the hammer at ten in the morning. At this point I imagined that even with a power hammer the job would take the best part of a day. The next morning I was a little disappointed to see that the council hammer was electrical - I had assumed it would be a medium sized jackhammer. My disappointment increased at the fountain itself. The fountain is in fact a large washtub, into which water from a tapped stream flows in and slowly out. The water is perhaps 18" deep. The washing surfaces which run the full length of both the long sides of the tub are at a medium angle - higher on the outside, lower on the water side. José and I were standing on the washing surfaces at the plaque end of the tub engaging in a certain amount of joking and horseplay in relation to the sloping surfaces, when there was a sudden change in his demeanour. Stepping down from the fountain he made a phone-call - apparently to the alcalde, at the end of which he said I couldn't have the hammer after all as it was needed for work elsewhere. This was clearly nonsense. I assumed this was some issue relating to 'health and safety' - an electric tool above a tank of water. Surely José didn't imagine I would work without setting up a platform first. There was a great deal of ire on display in the next few minutes. A medium sized jackhammer would see the job done in maybe two to three hours, an electric hammer would take double that, a cold chisel would see me into the night after a full day of July heat - I was livid that 'In this particular part of the world on this particular day a handshake is regarded as null and void.' I gave José a verbal hammering, he, irritated and adamant that the hammer was needed elsewhere, responded in kind. Setting up the scaffolding and starting work with lump hammer and cold chisel I was silently cursing José. Making little progress with the chisel and fully expecting a marathon of sweating I was surprised to notice that the concrete mix of the plaque was a little heavy on the cement side - a small tingle of potential delight fluttered into my thoughts. Concrete with too much sand typically does not crack - to be destroyed it has to be pulverised, by contrast concrete with too much cement has a tendency to crack easily. I wondered..... I fetched my sledgehammer. There was a little pause to consider potential consequences - the aim was to remove the plaque, without damage to the wall. Aware of the risk of the experiment I decided that the best target for the first blow was the Fascist symbol. Giving a full throttle swing with the sledgehammer I was delighted to see the entirety of the symbol shattered into pieces and falling into the washtub with that single blow. The wall behind was sound, with no sign of damage. No longer was I cursing José - his conduct was irrelevant - this method was likely to be quicker than with a jackhammer, let alone an electric hammer! The photograph of the plaque taken with part of the scaffold in view just before work started is timed 10.21am. the photograph taken with all equipment in the van and the wall cleaned of its filth is timed 12.37pm.  I poured some wine into a glass, sat on a nearby bench, and quietly drank a toast to my father, and to all the others who fought the Fascists. When I was little more than a toddler I engaged in some investigative experimenting. I remember for example seeking to discover why a model boat floated upright in water, also seeking to discover what material my bathtub was made of. Unfortunately I had not encountered at that age the concept of non-destructive investigation. Consequently by pulling away a section of the metal hull from the wooden superstructure to discover a beer bottle full of sand I effectively ruined the boat. Marginally less destructive was my removal of a handful of the top edge of my bathtub to discover some 'non-specific' fibrous material. My father, with exceptional unfairness, claimed on many an occasion that when I grew up I was destined to be a demolition expert. The removal of the Fascist plaque is a piece of demolition I believe my father would have fully approved of. I set off for the Council offices. On the way I passed José going in the opposite direction. We both stopped. He asked if I had finished the job. I showed him the before and after photos on my camera. We then drank a toast celebrating the removal of the plaque. The toast in three parts was led by me. I began "Primera - salud,", José responded "Primera - salud,", I continued "segundo - Franco es muerte," José responded "segundo - Franco es muerte," with a slight chuckle, I finished "tercero - el inscripción de Franco es muerte!" José with more of a chuckle, perhaps at my poor grammar, repeated "tercero - el inscripción de Franco es muerte!" (Primera - salud, segundo - Franco es muerte, tercero - el inscripción de Franco es muerte! First - health, second - Franco is dead, third - the inscription of Franco is dead!) I'm fairly sure the conversation ended with another handshake. What I'm quite certain about is that when it came to court José denied there had ever been an agreement to remove the plaque, denied there had been a meeting on the road, denied there had been a celebratory toast, and denied that he had assaulted one of the witnesses to the original agreement. In the afternoon when I was moving the rubble down to a spot next to the waste bins the Guardia Civil turned up. These two were young and indeed civil. A complaint had been made against me for removing the plaque - by the Alcalde! I explained the circumstances. I was asked if I had written proof of the agreement with the councillor. Well, no, it was an agreement sealed with a handshake, and In this part of the world a handshake is regarded as binding - isn't it? Or is an agreement sealed with a handshake just one more pile of rubbish?  Earlier I had been approached by a young woman who asked me not to remove the plaque as it was 'an important historical monument'. Later I was to discover she was related to a locally prominent Fascist. She was the only person foolish enough to describe the half-witted penis waving of the plaque as a 'historical monument'. As she fiddled with her mobile phone I asked her if it was a camera. "No." she lied. (To her credit she limited herself to telling the truth in court. Only three people in court told the truth, the others being myself, and a non-witness called as a result of the incompetence of the judge and the court appointed advocate.) When the widow of the Fascist era alcalde came on the scene we had a brief conversation. She said she was not bothered by the removal of the plaque, this in spite of efforts by the young woman to agitate her. The following day a villager came to see me. As they approached they performed a 'ritual' I have seen many others adopt since then. They stopped perhaps 10 metres away and made a full 360 degree turn to make sure no one else was in hearing distance before walking up to thank me for removing the plaque. They said that the plaque had been part of the scenery all their life, but they had never really looked at it, however now that I had removed it they were glad it was gone. Of the many local people who have thanked me only one was disinclined to be cautious - this curmudgeonly old so-and-so took an instant dislike to me, was always gruff and pointedly abrupt, however two days after the removal of the plaque he marched up bold as you like and announced "Fascistis, cabrones!" (this literally translates as 'Fascists are swine', but that doesn't quite match the vehemence of the sense). After that he was always as pleasant as could be. There is another plaque which should be removed, it too is an insult to both intelligence and decency. It is to be found polished, almost glowing in the entrance to the court house in Fonsagrada. Imagine the little girl who gets into her mother's bedroom and in time is found teetering around in high-heeled shoes, with a dress held up to prevent her tripping over, face smeared with lipstick, pretending to be an adult. Is that image in any way more ridiculous than having the name Manuel Fraga in pride of place in a court of 'justice'?  In the article 'Right back to the past' Josep Ramoneda writes (paraphrased) 'After Franco's death Manuel Fraga slipped easily into 'democratic' clothing, seeing no need to give any explanation at all for his past behaviour. Indeed he always prided himself on having worked for the dictatorship. Fraga, the regime's energetic propaganda chief and information minister, also played a role in the Spanish right's later attempts to whitewash the dictatorship. Fraga's death happened to coincide with the beginning of Judge Garzón's appearances in the defendant's dock. To watch a trial scene where the engineers of the Gürtel graft network and the heads of the Fascist party are cast as victims, and the judge who caught the grafters and defied the judicial taboo on the Fascist past is cast as their persecutor casts a deep shadow on Spanish institutions. It takes us right back to that Fascist past, and is incomprehensible to much of the foreign press. The flimsiness of the accusations against Garzón, not even supported by the public prosecutor; the tenacity of his pursuers; and the judge's well-known record project a deeply regressive image of Spanish justice.' No wonder Spanish 'justice' is the laughing stock of Western Europe. Meanwhile the little girl garishly attired and smeared imagines herself to be grown up. And Fraga's plaque seems to shine down with malign glee as costumed clowns play the ever amusing game of inverting logic. The infantile and intellect insulting pantomime of the court case is dealt with in various ways elsewhere on this web site. But there is one final point of interest, and of amusement and pleasure for me. The endless narrative from the Council was that they couldn't afford to do the work, hence my offer to do the job free of charge. When I made my offer I thought it possible the Council would refuse for Health and Safety reasons. Consequently I had it in mind to pay up to 500euros to enable them to do the job, should they decline my offer. As my offer to do the job simply for pleasure was accepted I made no mention of this second option. The court fine by chance happened to be the precise amount I had been willing to pay to get the job done, 500euros.... |

|

had the utterly ineffable delight  of swinging my sledgehammer! |

|

Postscript:- Years had passed when I answered a ring of the doorbell to find the widow of the Fascist era alcalde standing outside. She pointed a finger accusingly at me and said "I don't like you!" I imagined this was a much delayed response to the removal of the plaque - to my surprise it wasn't. She continued "I understand you have paid a visit to everyone who lives in the village. You haven't paid a visit to my house. I don't like this. You have to visit my house." With that she handed me a bag with home-cooked biscuits in it, and departed. Naturally, I paid the 'requested' visit, accompanied by a bottle of wine. |

|

|